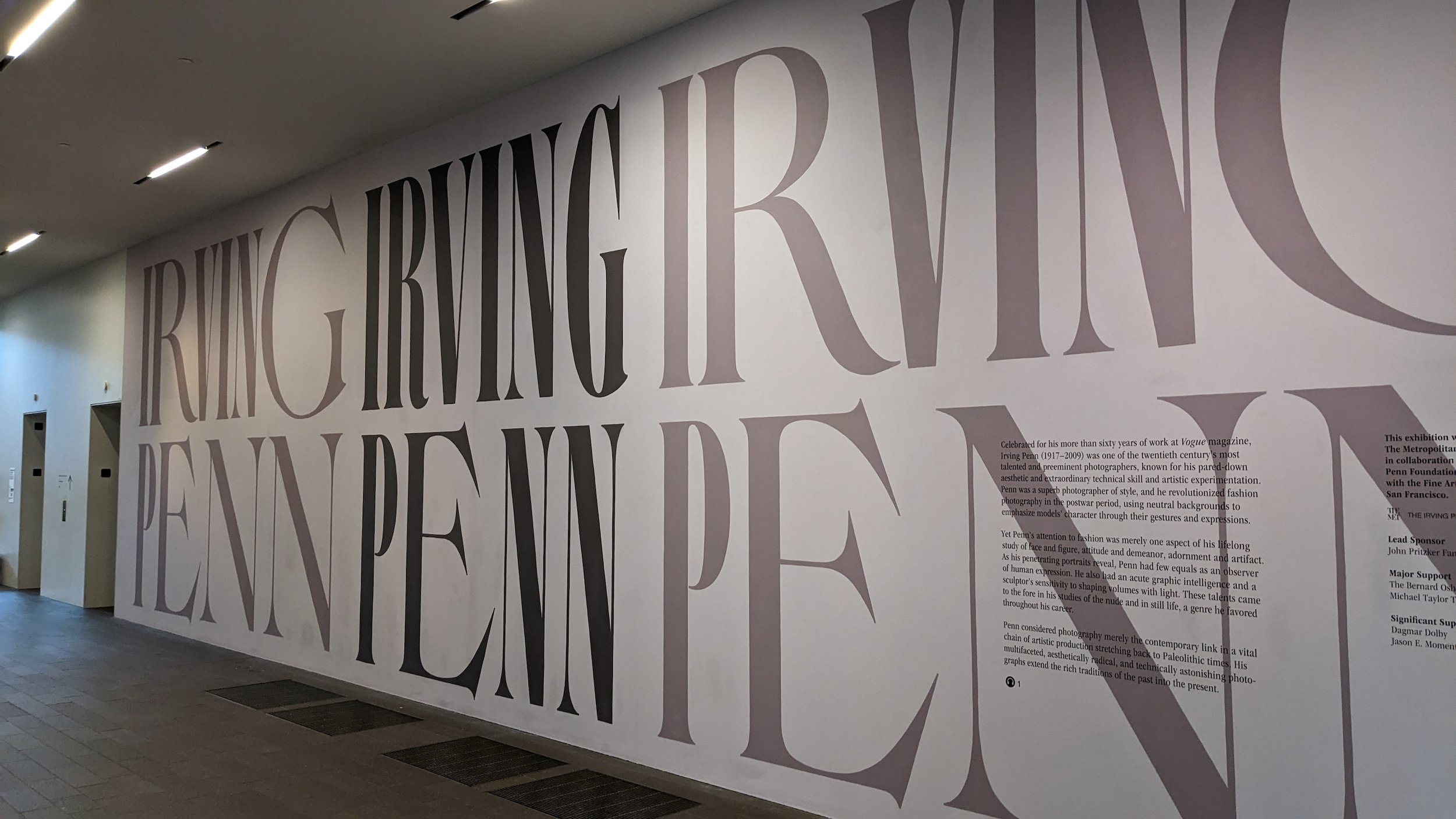

Irving Penn at the de Young

Entrance sign for the Irving Penn exhibition at the de Young Museum featuring boxer Joe Louis.

What do Ingmar Bergman, Alfred Hitchcock, Pablo Picasso, Le Corbusier, Salvador Dalí, and Jean Cocteau have in common? They were all photographed by Irving Penn, one of the 20th century’s most influential photographers. His portraits, fashion images, and still lifes turned simplicity into timeless art—and I recently got to see them at the de Young Museum in San Francisco.

The de Young Museum in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park.

Wall display introducing the Irving Penn exhibition.

Visitors explore the Irving Penn photography exhibition.

Exhibition copy of Irving Penn: Centennial.

Born in New Jersey, he first studied design before turning to photography. Over seven decades, he created some of the most iconic portraits of artists, writers, and everyday people. Penn’s minimalist style used plain backdrops and simple compositions to strip away distraction and emphasize gesture, texture, and presence.

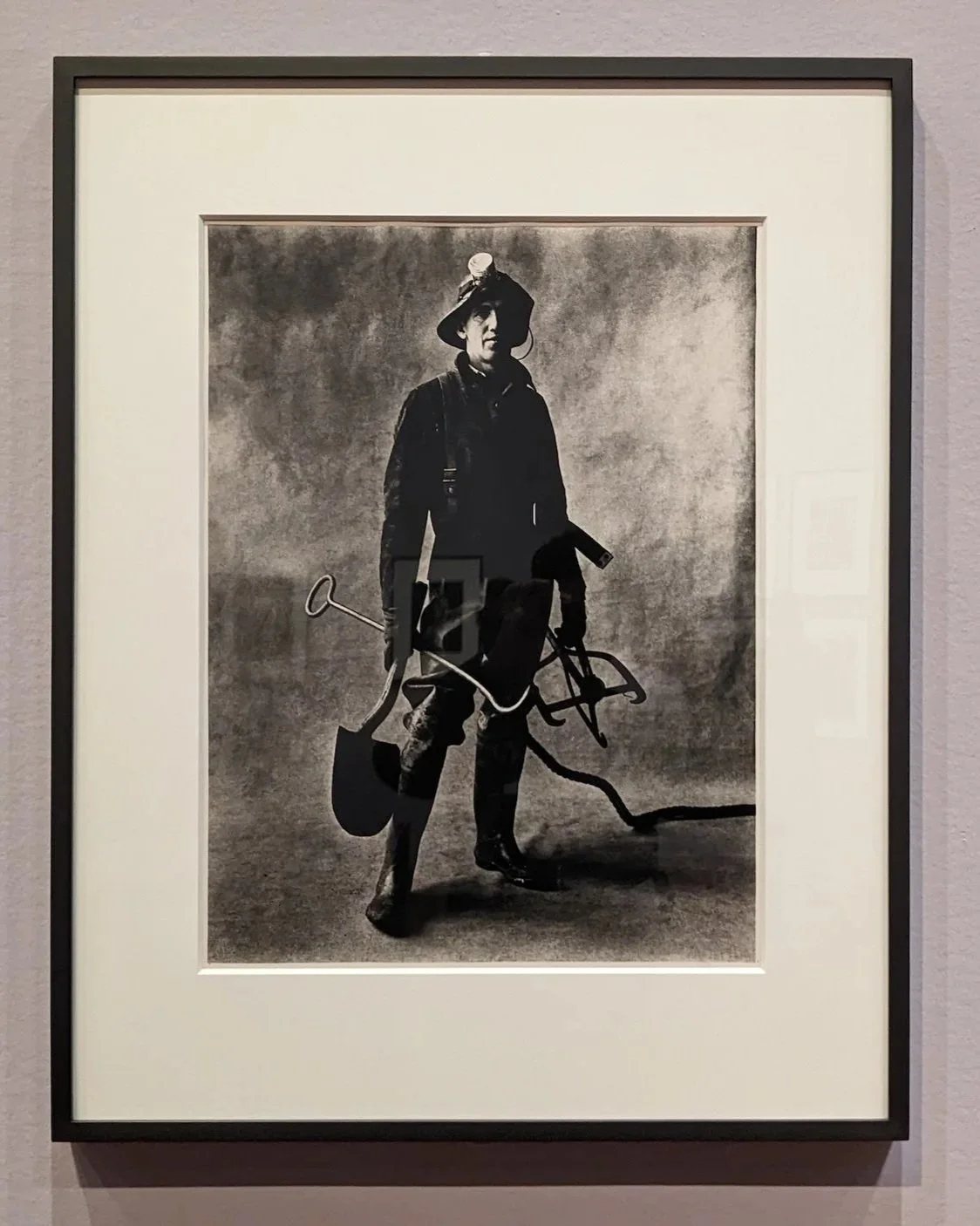

What I find most interesting about Penn’s work is that he didn’t only focus on famous figures—he also photographed everyday people with the same care and attention. His portraits of workers, tradespeople, and ordinary subjects show the same dignity as those of cultural icons.

Irving Penn’s photograph Coal Man, London, 1950.

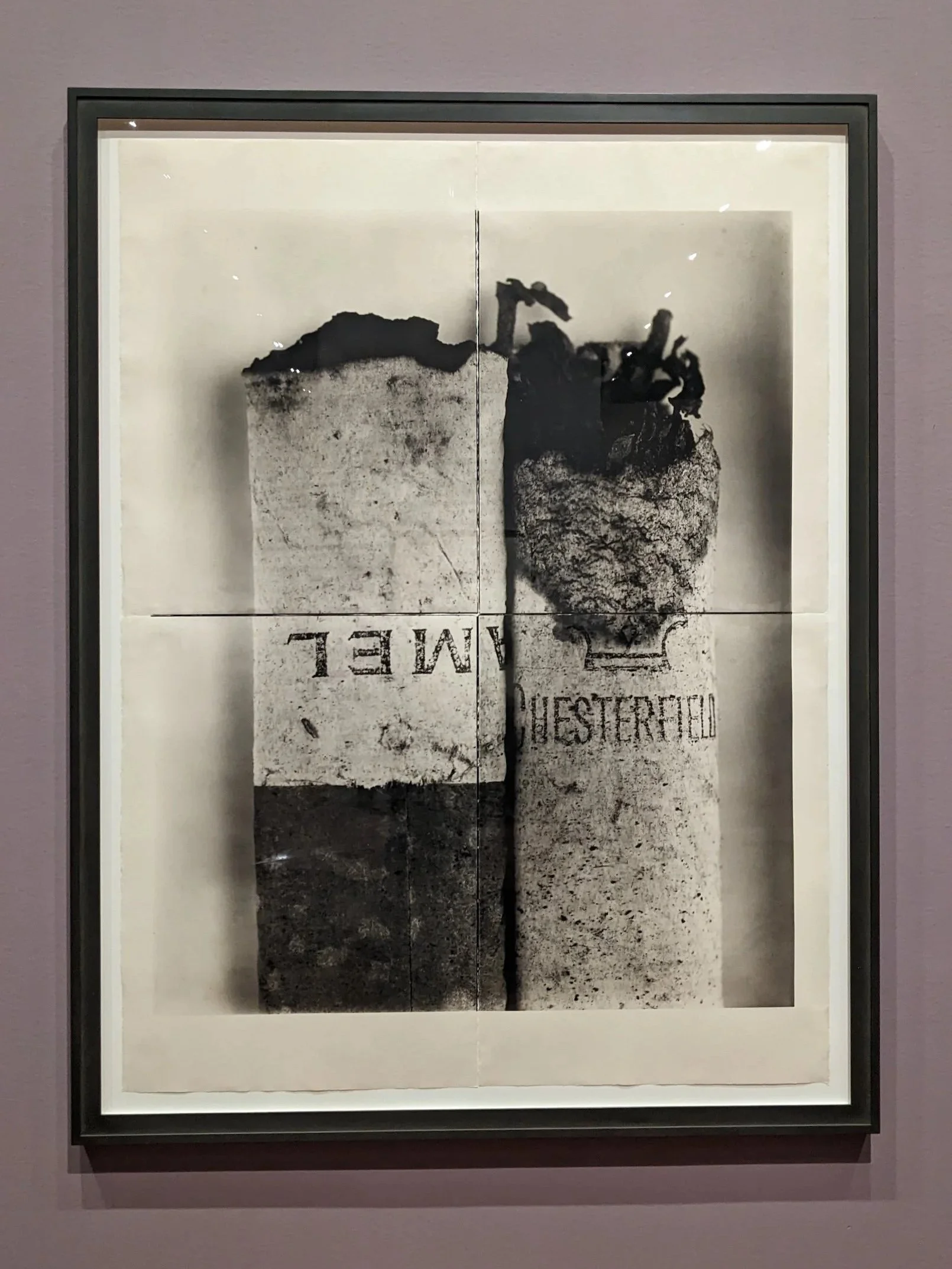

One of my favorite photographs of his comes from the cigarette series, where discarded butts are transformed into careful studies of shape and texture. These images reveal how even the most ordinary objects can hold unexpected beauty.

Irving Penn’s photograph of cigarette butts from his Cigarettes series.

After leaving the museum, I tried my own attempt at noticing beauty in discarded objects. I photographed a crushed Dr. Pepper can on the sidewalk, drawn to its shape, color, and distorted typography. I realized how much a small shift in attention can change the way we see.

Crushed Dr Pepper can on the pavement.

Banner for the Irving Penn exhibition at the de Young Museum.